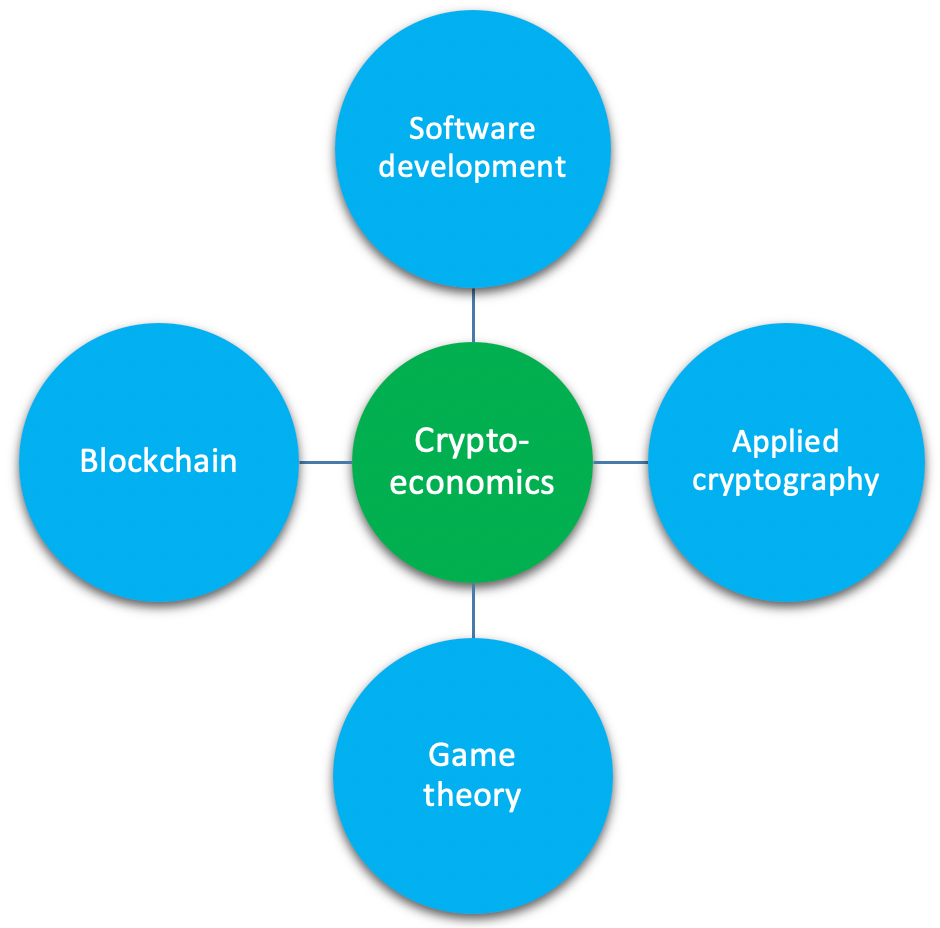

Blockchain technology and its cryptoeconomic governance structure are often considered to be the result of the combination of various disciplines, such as software engineering, game theory, computer networks and applied cryptography.

One discipline that is underemphasized, but that in my opinion should be included in crypto-economics, is philosophy. This post is a descriptive case study into Serey, a social blockchain inspired by a Rothbardian libertarian philosophy, and how it has aligned its philosophy with its technical governance structure.

1. Introduction

Although it’s manageable to develop applications without forming clear strategic philosophical alignment, it’s still recommended to develop a philosophical starting point that serves as a guide for actual implementation of blockchain technologies and the design of a cryptoeconomic governance structure.

The question I would like to answer in this post is how Serey, the first blockchain project in Cambodia, aligns its philosophy with its blockchain applications.

Section 2 discusses the relevance of philosophy in business decisions and to the development of blockchain applications. Subsequently, Serey is introduced. Serey is a social platform that is originally forked from the Steem blockchain. Its ambition is to engage users with their social decentralized applications (dApps), and to stimulate intellectual thought by offering users incentives to write and express their views freely without fear of being coerced or censored. Afterwards, I will discuss Serey’s philosophical perspectives that drive the Serey blockchain design, and describe how it has aligned its philosophical perspectives with its blockchain governance structure that includes (a) the right to decision making and blockchain maintenance, (b) incentives, and (c) accountability.

2. The relevance of aligning philosophy with blockchain applications

Ethical philosophy can serve as a blueprint for a blockchain’s operations, and embody values that are important for the founders and the community. The field of ethics concerns norms and values, and questions what is right and good, and how we can live a valuable life. The business ethicist, Christian Becker, puts forward three reasons why philosophy, in particular ethics, are relevant for businesses. Firstly, addressing ethical aspects can help businesses to identify new market opportunities and even competitive advantages. Secondly, users are increasingly aware of business ethics and hold certain ethical expectations that should be considered by businesses if they would like to appeal to the market. Lastly, philosophy helps business employees and founders to reflect on their operations and to turn businesses into a positive force of society. (Becker, 2019, pp. 7–8) Having ethical principles, can hence help the business to lay out a certain strategy and to have a guideline of what business practices to engage in. It is therefore highly recommended to develop a philosophical starting point when engaging in business and making business decisions, including decisions in blockchain applications development.

Looking at the Bitcoin blockchain, we can see that it has also been inspired by philosophical ideals first. It is the initial philosophy of decentralization that has determined that the Bitcoin attributes should be able to achieve certain societal ends, in line with particular philosophical assumptions of how society should be organized. These philosophical assumptions are libertarian in nature, and strive for a society with little or even no government interference in the economy and people’s lives. The goal of the crypto-anarchists[1] and cypherpunks[2] that have developed many of the technologies that have made Bitcoin possible, is visible from for example Wei Dai (personal communication, February 10, 1995), the creator of Bitcoin’s precursor, B-Money:

I’ve been assuming (perhaps incorrectly) for some time that most cypherpunks hold a belief somewhat like the following:

There has never been a government that didn’t sooner or later try to reduce the freedom of its subjects and gain more control over them, and there probably never will be one. Therefore, instead of trying to convince our current government not to try, we’ll develop the technology (e.g., remailers and ecash) that will make it impossible for the government to succeed.

Considering that the creation of ecash was merely a means to achieve certain ends like freedom from the clutches of government, and considering the fact that Satoshi Nakamoto regarded Bitcoin as an expansion of B-Money, it is reasonable to say that both cryptographic money systems stem from a shared philosophy.[3] Both cryptographic money systems embody an ethics that serve as foundational guidelines for the founders and the community.

As is the case with Bitcoin, Serey has also been founded on the crypto-anarchist and cypherpunk philosophy. Next, we will introduce Serey and see how this philosophy has shaped Serey’s technical blockchain design and its decisions on blockchain applications development.

3. Serey, a blockchain-based social platform

Serey is a social platform that is originally forked from the Steem blockchain, which was developed by Ned Scott and Dan Larimer in 2016. Like Steem, Serey also uses a Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS) consensus mechanism with a block time of 3 seconds. Serey is the first blockchain project in Cambodia, and has the ambition to stimulate intellectual thought by offering users incentives to write and express their thoughts. These incentives are both pecuniary and non-pecuniary in terms of Serey token distributions, and are discussed in greater detail in the section on Serey’s incentives structure. Other ambitions of Serey is to create a censorship-resistant platform on the blockchain level where everyone is free to enter and engage in sharing content and exercising their creativity, no matter what their social status or economic power is. Social applications that have already been developed or are currently in development on the Serey blockchain are a blogging platform (Serey.io), a marketplace, a lottery, and a question and answer application similar to Quora. From a user interface level, Serey aims for community-based censorship as a way to regulate what is visibly shown to users and to prevent content that is not in line with communal values.[4]

With respect to writing and sharing content, Serey believes that writing is one of the best ways to develop oneself intellectually. Through writing, you are forcing yourself to reflect on your own thoughts and to cultivate your imagination.[5]

The development decisions of the Serey applications follow strict libertarian principles. The Serey team has, for example, tuned their applications in such a way that they are congruent with the natural right of self-ownership from which other rights like the right to freedom of expression, the right to liberty, the right of voluntary association, and the right to property are derived. Next, I will elaborate on Serey’s philosophy.

3.1 What is Serey’s philosophy?

Serey starts with the deontological moral assumption that every individual has a natural right of self-ownership. From the right of self-ownership, the right of voluntary association, the right to freedom of expression, the right of secession, and the right to property are deductively derived. The argument runs as follows:

a. People have the right of self-ownership, based on the natural rights philosophy of Murray Rothbard;

b. If people have the right of self-ownership, they also have the right of voluntary association and freedom of speech;

c. The right of voluntary association implies the right of secession, which in itself is an important means to deal with the reality of value pluralism and the potential social conflicts that may result from it. One way to deal with this reality, albeit not perfect, is a participatory democracy;

d. If people have the right of self-ownership, they also have the right to keep the fruits of their labor;

e. In support of the rights mentioned above, people should uphold the principle not to aggress on these rights. This principle is called the non-aggression principle (NAP) or the anti-coercion principle.

I will elaborate more on the first statement (a). This statement can be supported by deducing natural law from the essential nature of human beings in a Rothbardian perspective. In For a New Liberty (1973), Rothbard writes that it is in man’s nature to use his mind in order to select values, ends and the means to attain these ends so that he can “act purposively to maintain himself and advance his life” (1973, p. 33). He furthermore contends that it is absolutely antihuman to interfere violently with a man’s “learning and choices” as “it violates the natural law of man’s needs” (1973, p. 33). Therefore, man’s nature should be protected through his right of self-ownership. This right asserts that man has the absolute right to “own” his body and “to control that body free of coercive interferences” (1973, p. 34). This right includes the practice of such essential activities as thinking, learning, valuing, and choosing ends and means without any coercion, since such activities are necessary for the enhancement of man’s life.

There are, I believe, three possible alternatives to self-ownership: either (1) nobody owns his own body, hence there is no self-ownership; or (2) a group or someone else entirely owns your body; or (3) everyone owns a part of everyone’s body. The first alternative can be countered with Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s argumentation ethics to show the inherent contradiction of the statement. Argumentation ethics is not much different from an argument that Rothbard has used in The Ethics of Liberty (1982) when he stated that “any person participating in any sort of discussion, including one on values, is, by virtue of so participating, alive and affirming life” (Casey, 2010, p. 42). In an argument on ethics whether self-ownership exists or not, it is impossible for the opponent of self-ownership to justify his opposition, because in arguing he already reflects his presupposition that he controls his body and mind exclusively. Hence his argumentative claims like “I think…” or “I believe…”. The “I”-form postulates that the “I” is a separate entity who is capable of controlling his own body, speech and mind. The ownership of one’s body is hereby verbally implied in one’s speech by taking a particular position in the argument (Hoppe, 1989, p. 158). Argumentation ethics is still a much debated concept within libertarian circles[6], however one could also claim that self-ownership is intuitively plausible: if you do not own your eyes, would that not give other people the right to take out your eyes?

The second alternative is that you do not own your own body, but instead your body is owned by someone else. This alternative denies universal ethics and asserts that there are subhumans who do not possess their own body (Rothbard, 1982, p. 45). It is implausible, because natural rights ought to be universally applicable for the simple fact that every man, for being human, must hold the same nature to use his body and mind in order to select values, ends, and the means to attain these ends. Moreover, there is a practical objection to this alternative. By arguing that someone owns your body you are implying your own slavery, a condition in which you are a subhuman, controlled by other humans.

Alternative 3 is the communal ownership of everyone’s body. Rothbard calls this condition “participatory communalism” (1973, p. 34). According to Rothbard, this is an absurd notion, because it would require everyone to gain approval of everyone else in order to take any action. Since it is impossible to gain everyone’s approval, it would freeze all human action which would result in the extinction of man. (1973, p. 34) As natural rights exist for the preservation of the human race as well as for “what is best for man and his life on earth”, alternative 3 should be rejected (Rothbard, 1973, p. 34). By rejecting the three alternatives to self-ownership, we can therefore conclude that everyone has the natural right of self-ownership.

From this natural right follows the right to do anything with one’s body, including the right to form free associations and communities, and the right not to be violated in one’s self-ownership.[7] Thus, one has the right to associate oneself with the leader of one’s choice, but not the right to impose a leader unto someone else. Likewise, people should be free to join and to leave communities voluntarily. This is particularly important from the perspective of social conflicts. Bernard Williams has likewise stated in In The Beginning Was The Deed (2005) that political philosophy “is to an important degree focused in the idea of political disagreement” (Williams, 2005, p. 77) and that “political disagreements include disagreements about the interpretation of political values, such as freedom, equality, or justice” (Williams, 2005, p. 77). One substantial focus of political philosophy is hence on value pluralism and the conflicts that emerge from differing political ideas (Galston, 2010, p. 13). What is attractive about participatory democracy is that it engages the community to give shape to their functioning environment in a communal fashion. In other words, it is a strong social model to deal with the realities of value pluralism. However, we must also be wary of attributing “to the voice of the people a kind of final authority and unlimited wisdom” (Popper, 1963, p. 347). When society holds a vox populi vox dei attitude, it can easily slip into a tyranny of the majority. In that sense, people should always be allowed to exercise their right of voluntary association and secede from their community.[8] In the case of cryptocurrencies, this practically means that people should be allowed to join any blockchain community along the lines of their comprehensive doctrines[9], and also peacefully secede from an existing blockchain community.[10]

In addition to the right of voluntary association, people also have property rights. Rothbardian property rights are directly derived from self-ownership rights, and are based on the Lockean homesteading theory (Casey, 2010, p. 49). It states that since man owns his person, he owns his labour, and therefore he also owns the fruits thereof. John Locke (1689) has put homesteading theory in the following way:

… every man has a property in his own person. … The labour of his body and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state of nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined it to something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property. (Rothbard, 1973, pp. 37–38)

Given that man has the right of self-ownership, and that he must employ natural objects for his survival, “then the sculptor has the right to own the product he has made” through the “mixing of his labour” (Rothbard, 1973, p. 37). In other words, by producing something with one’s energy through the utilization of unowned nature, one has “placed the stamp of his person upon the raw material” (Rothbard, 1973, p. 37). One therefore rightfully owns the product. Any violation of self-ownership and property rights should hence be regarded as an act of aggression.

In the next section, I will clarify how Serey has aligned this libertarian philosophy, which includes the rights to self-ownership, voluntary association, secession, freedom of expression, and property, with its business practices and its governance structure.

3.2 How Serey’s philosophy is aligned with its governance structure

In this section, I put forward how Serey, guided by its libertarian philosophy, aims to achieve intellectual stimulation and freedom of expression through the use of blockchain technology in its social applications, and how Serey’s philosophy is congruent with its governance structure. First, I would like to discuss why blockchain has been chosen as a technical solution at all.

3.2.1 Blockchain as the means to stimulate freedom of expression

A blockchain is in essence a public global ledger that is distributed among a network of computers. It consists of data blocks in which transactions are recorded. Every computer on the network continuously synchronizes its local blockchain version with the latest state of the public ledger. Due to its distributed nature, it is also immutable — if someone would like to modify the blockchain, it has to be accepted by the majority of other computers on the network. Each block of a blockchain contains several attributes like a version number of the software, a nonce, a timestamp, a hash, a ‘previous hash’ and so on. The hash of a block is the result of a number of attributes that are run through a hashing algorithm, resulting in an output of a fixed length. This output, the hash, serves as a digital fingerprint of the block. Each addition, removal or modification of a character in the attributes’ data cascades in an entirely different hash.[11] Hence, if someone changes data within a block, other computers on the network can recognize that the block with the modified data is tampered with by only looking at the hash change. The ‘previous block’ attribute of a block refers to the hash of the previous block. Doing so, each block is linked to a previous block. Changing the data within a block results in a change of the hash of the current block, and in the alteration of all subsequent block hashes. (Chauhan, Malviya, Verna, and Mor, 2018, p. 2) In order to keep focus on the main topics of this post — the alignment of applied philosophy and the blockchain applications of Serey — it suffices to provide this rather simplified description of a blockchain.

The immutability property of blockchain is particularly interesting for Serey, as it records people’s posts on the blockchain in order to enable censorship-resistant social platforms. Doing so, Serey can be an instrument of uncensored speech on the blockchain level, and hence promotes freedom of speech — something that is still not widely accepted in many countries. The word “Serey” [សេរី], therefore also fittingly means “liberty” in the Khmer language. It makes it harder for governments and trusted third parties like Facebook and Twitter that own and run centralized social platforms to crack down on people’s freedom of expression. Utilizing blockchain technology, Serey thus respects the philosophical standpoint that people should have the right to freedom of expression.

Next, we will investigate the Serey governance. Governance is defined by Peter Weill as the framework of decision making and responsibilities to stimulate preferred behavior (2004, p. 3). I distinguish three elements of governance that I will further elaborate in the context of Serey, while aligning it with Serey’s philosophical standpoint as elaborated in section 3.1:

1. Rights to decision making and to maintain the blockchain;

2. Incentives;

3. Accountability.

3.2.2 Rights to decision making and to maintain the blockchain within Serey

Among the rights to decision making, are the rights to submit improvement proposals, to execute the proposals and to monitor the proposals. These proposals can affect the protocol, but do not necessarily have to. These rights can be arranged in a centralized or decentralized manner. (Beck & Müller-Block, pp. 10–11). In other words, is the power of decision making concentrated within one party, a small group of parties or is it spread out over a larger decentralized network? In addition, who should be the ones to maintain the blockchain and be involved in block validation?

With respect to the decision making in improving the Serey network, the network went live in the second quarter of 2018, and is therefore still a young startup. It has not conducted an ICO, and its development thus far has been mainly financed by the founders. As with young blockchain startups with modest financial means, the blockchain started relatively centralized with one development team improving the protocol, determining what improvements to be made, and developing the ecosystem. Once the main network proved to be more stable, which happened since the large chain update of Q4, 2019, efforts had been made to further decentralize the blockchain and increase community involvement in the blockchain maintenance. The number of active block producers has been increased to 20. This makes the DPoS consensus mechanism of Serey similar to that of, for example, the Steem, BitShares and EOS blockchains that also have a somewhat similar number of active block producers.

The decision for the Serey team to choose DPoS over PoW and PoS is based on the realization that blockchains suffer from a scaling trilemma. The trilemma maintains that there are three properties of a blockchain that cannot ideally be fulfilled simultaneously. These properties are (a) decentralization, (b) scalability, and (c) security.

Decentralization is defined as a property of no single point of failure. The more decentralized a blockchain is, the greater the number of validating nodes on the network.[12] However, there are tradeoffs to highly decentralized blockchains. They are also less scalable, lest they are willing to compromise on security or forgo on-chain registration of transactions by, for example, the implementation of layer 2 solutions. Layer 1 is where blocks are created and chained to one another. (Qin & Gervais, 2019, pp. 3–4) Scalability is related to the transaction throughput in seconds and other factors that determine the speed of a blockchain like latency and bandwidth. (Yli-Huumo, Go, Choi, Park & Smolander, 2016, p. 21) More decentralization leads to slower network propagation, longer settlement times, and worse user experience. The block size, block time, the permissionless nature and relatively high decentralized blockchain of Bitcoin (BTC) has resulted in a slow network that is only able to handle 7 transactions per second (Qin & Gervais, 2019, p. 4). Serey has therefore chosen for a consensus mechanism, DPoS, that makes the tradeoff to only allow a fixed set of participants to validate and produce the blockchain.

DPoS can be best compared to a non-coercive technology-based representative democracy in which users continuously vote on witnesses. The democratic structure of DPoS suits Serey’s argument that democracies are a powerful means to deal with the reality of value pluralism. It is non-coercive, because users are not forced to participate in the witness election, and if one does not like to make use of the Serey services one can always opt out. The Serey tokens are considered stake that can be used to vote on block producting nodes, also called witnesses. The election process runs as follows:

a. Each person that would like to become a witness, can set up a witness node and run a community campaign to receive votes. It is highly recommended for aspiring witnesses to make positive contributions to the community and the network, in order to receive the most number of votes. Votes are weight-based on the total number of stake a user has.

b. Users, holding Serey tokens, can allocate their tokens as votes to witnesses. Each token is considered one vote. Users can vote anytime of the day.

c. Every two weeks, the top 20 aspiring witnesses with the most votes become active witnesses and are allowed to produce blocks. In addition to the 20 active witnesses, there is one reserve witness which is randomly chosen from all the aspiring witnesses that are outside of the top 20.

The active witnesses take turns in producing blocks with block intervals of 3 seconds. First, it’s witness 1 that produces a block, then it’s witness 2, then witness 3 etc. After the reserve witness, witness 21, has produced a block, the block production process starts all over again with witness 1. It is thus already determined who will create the next block. This makes the Serey blockchain much more scalable. Serey can therefore process around 3,300 transactions per second with short settlement times of maximum 3 seconds. Compared to PoW, it is less financially demanding on the user as it does not require investments in computing power. DPoS blockchains are therefore known to be more energy efficient than the Proof-of-Work (PoW) mechanism that is used in for example Bitcoin and the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) mechanism (Minxiao, Xiaofeng, Zhe, Xiangwei & Qijun, 2017, p. 2568).

Serey believes that this technology-based democracy model is also suited to a social platform that incentivizes users to make good decisions and show good behavior in the benefit of the whole community, and that tries to keep users accountable for their decisions and behavior.

3.2.2 Incentives

A blockchain with a well-developed incentives structure, encourages users to behave in such a way that their behavior is in line with the blockchain system. (Beck & Müller-Bloch, 2018, pp. 11–12) Participants of the Serey blockchain are encouraged to engage with the blockchain by submitting content to it, being involved with the DPoS election process or by running witness nodes. Incentives for participation can be divided in (a) pecuniary and (b) non-pecuniary measures.

The technology-based democracy model of DPoS is extended to the pecuniary rewards mechanism for content, assuming that Serey tokens do indeed have pecuniary value. Every post, made by a user, can be upvoted or downvoted. In general, the more upvotes a post receives, the higher the rewards. What also matters is the people and the number of shares they hold, in terms of Serey tokens, when they upvote the post. If a post is upvoted by someone with more Serey tokens, the impact on eventual rewards is higher than if the post is upvoted by someone with less Serey tokens.[13] These rewards are subsidized by the blockchain through the annual 1% inflation of the total number of Serey tokens.

An example of a non-pecuniary incentive is providing privileges and status increasing visibility to those who display good behavior. For this purpose, Serey makes use of visible reputation scores. The score indicates how appreciated the user is by the community. In Serey, the reputation score is a Log base 10 function. When an author’s content is upvoted, it impacts the author’s reputation. The impact is dependent on the reputation of the voter, and the share of the voter’s rewards which he receives for his effort in content curation.[14]

Due to the logarithmic function, a reputation score of 60 is 10 times stronger than a reputation score of 59. In addition to visible reputation scores, the curation algorithm also serves the content ranking system. Posts that are upvoted more often, are not only more likely to receive higher rewards, but the post also climbs towards the top of the page for better visibility. As the impact of a user’s vote is also dependent on the number of Serey tokens the user possesses, the user is even more incentivized to collect Serey tokens. These are all incentives for users to make positive contributions to the platform.

Another important feature of the Serey social platform, is that it respects the users’ right to property. Supposing that the user’s content is the product of his own ingenuity and creativity, similar to how a worker mixes his labour with nature in Locke’s homesteading theory, we could say that the user therefore ideally should have the right to keep the fruits of his content. Following this perspective, rewards in Serey tokens are added to the user’s wallet without any possibility of a third party to plunder the user’s wallet. Each Serey wallet comes with an owner key that is known only by the owner of the wallet. In this regard, Serey also respects the people’s right to property and the people’s right to keep the fruits of their labour.

3.2.3 Accountability

Accountability is related to the right to monitor decisions and behavior, and to hold people accountable for their decisions and behavior. Accountability can be implemented and exercised through contracts and behavior protocols that are written down in the blockchain software. (Beck & Müller-Bloch, 2018, p. 11)

Content posted on Serey, is fully transparent for anyone else to see. The way accountability is encouraged on Serey also revolves around democratic participation. Users that place inappropriate or bad content, can be downvoted by the community. Downvotes results in (a) less pecuniary rewards in terms of Serey tokens, (b) lower reputation scores, and © les visibility of posts. This also stimulates users to engage with one another in a reasonable and civilized manner. Trolling is discouraged, because trolls can be downvoted, making them less visible.

It’s important to realize that although Serey promotes censorship-resistance on the blockchain level, the community can still influence which posts are more visible and which less. Hence, we can assert that there is community-based censorship on the web interface level. The community-based censorship attribute is important for Serey as it is in line with Serey’s philosophical view that people have the right to secede from an existing community, to form voluntary associations along the lines of their personal comprehensive doctrines, that social problems should be solved as much as possible by the community in a decentralized fashion, and that solutions to social problems should reflect the values of the community as much as possible. If someone does not like the main social platform of Serey, the person is allowed to disengage with the social platform and set up his own dApp, connected to the Serey blockchain, and determine what content from the blockchain is shown and which users are allowed. Serey cannot interfere with how users conduct their relationships with other users on the platform. They cannot determine who users should vote for, nor can they determine with whom people should interact.

4. Conclusion

In this post, I have provided a case study on the alignment of applied philosophy and Serey’s blockchain applications. Although philosophy is still underemphasized in blockchain research, I believe that addressing it can help businesses to identify market opportunities and competitive advantages. Philosophy also helps businesses to reflect on their operations and to guide them in deciding what directions to take with respect to the development of blockchain applications. Serey governs their blockchain applications with a philosophy that principally starts with the right of self-ownership from which the following rights are deduced:

a. The right of voluntary association and freedom of speech;

b. The right of secession;

c. The right to keep the fruits of your labor;

d. The right not to be aggressed on the above mentioned rights.

Serey’s choice of using DPoS blockchain technology is well in line with their aspirations to stimulate uncensorable intellectual thought and the right to freedom of expression through a mix of pecuniary and non-pecuniary incentives. Although the non-coercive technical democracy of Serey provides a proper means to deal with the realities of value pluralism, it also adheres to Serey’s philosophy to allow users to secede from the existing community along the lines of their personal comprehensive doctrines, to form voluntary associations, and to develop applications on top of the Serey blockchain that are more in line with the values of the user. On the blockchain layer perspective, everyone has equal access and the blockchain provides transparency and censorship-resistance for all. On the application level perspective, however, Serey leaves room for users who start their own dApps to have community-based censorship models. Thus, we can see that Serey’s ethical philosophy has clearly permeated into their application designs and their governance structure.

References

Arcange. (2017). What is Steemit reputation and how does it work? Retrieved from https://steemit.com/steemit/@arcange/what-is-steemit-reputation-and-how-does-it-work

Assange, J., Appelbaum, J., & Müller-Maguhn, A. (2012). Cypherpunks: freedom and the future of the internet. New York: Or Books.

Beck, R., & Müller-Bloch, C. (2018). Governance in the Blockchain Economy: A Framework and Research Agenda. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 19(10), 1020–1034. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00518

Becker, C. U. (2019). Business Ethics: Methods and Applications. New York: Routledge.

Buterin, V. (2017, February 6). The Meaning of Decentralization. Retrieved on 28 February 2020, from Medium website: https://medium.com/@VitalikButerin/the-meaning-of-decentralization-a0c92b76a274

Buterin, V. (2017, March 15). Hard Forks, Soft Forks, Defaults and Coercion. Retrieved on 27 February 2020, from Vitalik.ca website: https://vitalik.ca/general/2017/03/14/forks_and_markets.html

Casey, G. (2010). Murray Rothbard. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Chauhan, A., Malviya, O.P., Verma, M., & Mor, T.S. (2018). Blockchain and Scalability. IEEE International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security, 2018. doi: 10.1109/QRS-C.2018.00034

Galston, W.A. (2010). Realism in Political Theory. European Journal of Political Theory, 9, 4, 385–411.

Hoppe, H.H. (1989). A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism. Retrieved from https://mises.org

Locke, J. (1689). Second treatise of government: an essay concerning the true original, extent and end of civil government. Arlington Heights: Harlan Davidson.

May, T. (1988). Crypto Anarchist Manifesto. Retrieved from Satoshi Nakamoto Institute website: https://nakamotoinstitute.org/crypto-anarchist-manifesto/

Minxiao, D., Xiaofeng, M., Zhe, Z., Xiangwei, W., & Qijun, C. (2017). A Review on Consensus Algorithm of Blockchain. IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), 2017.

Murphy, R.P. & Callahan, G. (2006). Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s Argumentation Ethic: A Critique. The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 20, 53–64.

Murphy, R.P., & Callahan, G. (2006). Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s Argumentation Ethic: A Critique. Journal of Libertarian Studies, 20, 2, 53–64

Nietzsche, F.W. (1889). Twilight of the Idols or, how to philosophize with the Hammer (R. Polt, Trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Popper, K. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations. London: Routledge.

Qin, K., & Gervais, A. (2019). An overview of blockchain scalability, interoperability and sustainability. EU Blockchain Observatory & Forum.

Rawls, J. (2001). In Justice as Fairness: A Restatement. Foreword. Kelly, Erin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rothbard, M.N. (1973). For a New Liberty: the libertarian manifesto. Retrieved from https://mises.org

Rothbard, M.N. (1982). The Ethics of Liberty. Retrieved from https://mises.org

Sultan, K., Ruhi, U., & Lakhani, R. (2018). Conceptualizing Blockchains: Characteristics & Applications. 11th IADIS International Conference Information Systems, 2018, pp. 49–57.

Weill, P. (2004). Don’t just lead, govern: How top-performing firms govern IT. MIS Quarterly Executive, 3(1), 1–17.

Williams, B. (2005). In The Beginning Was The Deed: Realism and Moralism in Political Argument. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Yli-Huumo, J., Ko, D., Choi, S., Park, S., & Smolander, K. (2016). Where is Current Research on Blockchain Technology? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE, 11(10). Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163477

[1] Timothy May, who introduced the basic concepts of crypto-anarchism in his ‘Crypto Anarchist Manifesto’ (1988), described it as a form of digital anarchy brought about by cryptographic technology, ensuring anonymity, freedom of speech and freedom to trade.

[2] Julian Assange defines cypherpunks as “activists who advocate the mass use of strong cryptography as a way protecting our basic freedoms” (2012).

[3] Satoshi Nakamoto writes to Wei Dai on 22 August 2008:

I was very interested to read your b-money page, I am getting ready to release a paper that expands your idea. Adam Back (hashcash.org) noticed the similarities and pointed me to your site.

[4] More details regarding community-based censorship, in section 3.2.3.

[5] Friedrich Nietzsche had likewise asserted that learning how to write and to express oneself should be taught to stimulate the intellect. He had argued in Twilight of the Idols (1889):

For we cannot subtract dancing in any form from noble education, the ability to dance with feet, with concepts, with words: need I add that one must also be able to dance with the pen — that one must learn to write? (p. 49)

[6] See for example ‘Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s Argumentation Ethic: A Critique’ (Murphy & Callahan, 2006).

[7] This is also known as the libertarian non-aggression principle (Rothbard, 1974, p. 116).

[8] Even governmental leaders in representative democracies are chosen to govern people who have not explicitly consented to be governed, i.e. they are to a certain degree imposed on all citizens. Representative democracies are therefore not representative of the whole constituency (Casey, 2012, p. 128). It is, therefore, important that people can exercise their right to secede.

[9] A comprehensive doctrine is defined by John Rawls as a person’s set of values and concerns. Rawls accepts that it is an inevitable reality that people hold different comprehensive doctrines, and that in order to deal with the reality of value pluralism, we should look for sufficient commonalities that serve as the foundation for overlapping consensus. (Kelly, 2001, p. xi)

[10] Secession in the blockchain space is analogous to a hard fork. Vitalik Buterin writes in ‘Hard Forks, Soft Forks, Defaults and Coercion’ (2017) that the essential difference between hard forks and soft forks is that “soft forks clearly institutionally favor coercion over secession”. With a soft fork, the user is “coerced into accepting a change in protocol rules”, whereas a hard fork provides more user freedom by allowing the user the option to opt out of an existing blockchain protocol.

[11] A proper hash algorithm should also be deterministic, make reverse engineering of the hash output into its data input impossible, convert the data input into a hash output quickly, and minimize the probability of hash collisions.

[12] Although this is the most commonly used definition of decentralization, there are different ways to look at decentralization. Vitalik Buterin, for example, makes the distinction between architectural, political and logical decentralization. (2017)

[13] Stake-based voting hence plays a major role in Serey. It encourages users to accumulate more Serey tokens.

[14] A user can also earn rewards for upvoting content. The author of the content shares the rewards with the curators.

Comments